What was the research? Here is a summary of what they did. "Respondents were first asked the favorability question, and then shown selected video sections of each of the advertisements to ascertain whether or not they had seen them before. The brand favorability scores were then split between those who recognized and those who did not recognize the advertisement. This produces a "shift" in favorability (referred to below as Fav-Shift) that indicates the extent to which the advertising has improved the brand relationship while on air."

Heath's error here is to confuse correlation with causation. He has found a relationship between two variables, and jumped to the assumption that one 'caused' the other.

Let me explain. When respondents say the recognise an ad, it does not mean that they have necessarily seen it. I once saw 80% recognition for an ad which had not aired, because respondents confused it with another ad. And when they say they do not recognise an ad, it does not necessarily mean they have not seen it. They may have seen it and had forgotten having seen it.

This second part is particularly important, because - the more familiar you are with a brand, the more likely you are to notice and remember its advertising. This isn't just an issue of splitting out brand users. If you take non-users, there will be different degrees of familiarity - some will have used the brand in the past, some will have friends who use it, while others will not have heard of it, etc.

So - if you look at a group of people who recognise an ad, they are likely to be more favourably disposed towards it, just because of this phenomenon. It does not mean the advertising has had an effect.

I'll give you an example.

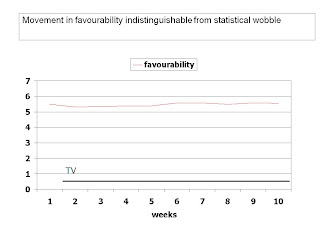

Here is a brand which you've got to feel a bit sorry for. It has had over 1300 GRPs spent behind it over this period. Yet the movement in brand favourability (among non-users) is indistinguishable from the wobble evident at the very start of the chart, before the advertising begins.

Yet, just focusing on non-users, looking at ad-recognisers v non-recognisers, brand favourability among those who did not recognise the ad was 5.65. Among those who did recognise one of the ads it was 6.15. (On a ten point scale) . This would represent a substantial rise in favourability. If you relate this shift to what actually happened on the chart above, you'll see it represents a massive over-statement of the effectiveness of the ad.

What we have here is a variant of the Rosser Reeves fallacy, discovered back in the 60s.

This highlights why comparing the views of recognisers v non-recognisers is not a reliable way to look at the effectiveness of advertising. Even among non-users.

And means that the Heath, Brant, Nairn research was fundamentally flawed and worthless.

P.S. A paper by Heath and Hyder in 2004, "Measuring the Hidden Power of Emotive Advertising"according to Heath, called "into question the value both of recall metrics and

continuous tracking research."

But this research was also based on this recognised/non-recognised analysis. so is equally worthless.

No comments:

Post a Comment