Friday, 5 December 2008

Affect and Cognition

When Robert Heath writes: "Damasio and others have confirmed that, when it comes to decisionmaking, Affect (i.e. feelings and emotions) always dominate Cognition (i.e. thinking)" is is worth remembering what Damasio actually wrote: " never wished to set emotion against reason, but rather to see emotion as at least assisting reason...nor did I ever oppose emotion to cognition since I view emotion as delivering cognitive information." and "I suggest only that certain aspects of the process of emotion and feelings are indispensable for rationality." Descarte's Error

von Daniken

Erich von Däniken is a controversial Swiss author best known for his books which present claims of evidence for extraterrestrial influences on early human culture, most prominently Chariots of the Gods?, published in 1968.

His work misused archaeological evidence, studies of religion, and of art to make his case. Evidence which countered his arguments was ignored.

Most in the scientific community have ignored or dismissed von Däniken's hypotheses.

For some reason, he reminds me of Robert Heath.

By 1982 he could not find an English or American publisher for his tenth book.

His work misused archaeological evidence, studies of religion, and of art to make his case. Evidence which countered his arguments was ignored.

Most in the scientific community have ignored or dismissed von Däniken's hypotheses.

For some reason, he reminds me of Robert Heath.

By 1982 he could not find an English or American publisher for his tenth book.

Attention and Emotion

In a presentation "HOW DO WE PREDICT ATTENTION AND ENGAGEMENT?"

Robert Heath quotes Du Plessis as saying ‘…there is little doubt ad-liking has an effect on the ability of a commercial to get attention…’

And quotes Page: ‘… we pay more attention to emotionally powerful events’

He dismisses these, saying Du Plessis and Page's error was to "Assume SYSTEMATIC & GOAL-DRIVEN TV processing"; while "in real viewing situations processing is AUTOMATIC & STIMULUS-DRIVEN".

Actually, Heath's error is to pretend that Du Plessis and Page were theorising. Instead, both were reporting patterns in different data sets.

Page was reporting on 150 US ads, which were split into three groups based on their ability to generate an emotional response among viewers. This was then related to the average level of involvement these ads generated, as measured on Link.

Du Plessis was reporting on analysis of 11400 South African ads; pre-testing had measured ad likability, while tracking had measured recall of the ads, three weeks after they went on air.

Because it completely contradicts his theries, Heath has to ignore this data, so he can rely on claiming that any assertion that emotional content relates to higher attention is just an untested supposition, hence his quotes:

"a link between emotion and attention is also a popular belief."

"Ray & Batra (1983) speculate that ‘People may pay more attention to affective advertising’

"The main task of creativity is generally believed to be to get people to pay attention"

Recall and Persuasiveness

In 'Measuring the Hidden Power of Emotive Advertising' Heath asserts: "The belief underlying recall-based metrics is that advertising has to be persuasive in order to be effective."

This is another of Heath's errors.

Data from Millward Brown shows that there is no correlation between the persuasiveness of an ad and its Awareness Index (their measure of the ad's memorability).

In other words, ad recall has nothing to do with ad persuasiveness.

A Millward Brown Admap paper "An analysis of how effectively advertising research can predict sales" reports that a higher Awareness Index is related to more enjoyable, more involving advertising, and shows from data (rather than argues from theory) that ads which focus on emotional content have higher Awareness Indices than ads with rational content.

This is another of Heath's errors.

Data from Millward Brown shows that there is no correlation between the persuasiveness of an ad and its Awareness Index (their measure of the ad's memorability).

In other words, ad recall has nothing to do with ad persuasiveness.

A Millward Brown Admap paper "An analysis of how effectively advertising research can predict sales" reports that a higher Awareness Index is related to more enjoyable, more involving advertising, and shows from data (rather than argues from theory) that ads which focus on emotional content have higher Awareness Indices than ads with rational content.

Liking and Attention

This past year Robert Heath has presented, on a number of platforms, research which he claims shows "THE MORE EMOTIVE AN AD …

THE MORE YOU LIKE IT…THE MORE YOU TRUST IT…THE LESS ATTENTION YOU PAY TO IT"

This continues the theme he has plied for nearly ten years now; but the research is new.

He starts with the understanding that eye movements are ideal for measuring attention levels. Tiny totally autonomic rapid reflex movements, known as fixation speed. This is an approach which has been used successfully with static stimulus, such as print, in the past. But he uses it for TV ads. And it is from this work that he concludes that the more you like an ad, the less attention you pay to it, and "High levels of emotional content in advertising were significantly correlated at 99.9% with LOWER levels of attention"

This fits perfectly with his theory, yet flies in the face of all the other research into this topic.

Why should this be?

I don't know. But - I suspect the answer lies in one sentence of his papers (e.g.‘KRUGMAN WAS RIGHT – TV ADVERTISING GETS LITTLE ATTENTION BUT BUILDS BIG BRANDS’) . "A few subjects started by watching the screen carefully and followed the action, but most watched in a ‘lazy’ way, exactly matching Krugman’s description of ‘motionless, passive eye characteristics’."

In other words, the thing he was measuring, eye movements, stopped being measurable a few moments into the ad, because the eyes became motionless. So the only way he could distinguish between the levels of attention paid to different ads was through the responses picked up at the start of each ad.

So, if Heath's sentence is an accurate summary, we have the inference that his assessment of the level of attention paid to the ads was actually a measure of the attention paid to the first few moments of the ad.

Can this be right? Surely if this were the case, he would have highlighted the fact in the papers? But none of them refer to it.

There is one other factor here worth reporting on. In his most recent paper, he refers to the r squared for the relationship. This is a measure of how close the relationship is; an r squared of 0 shows there is no relationship between the measures, an r squared of 1 shows there relationship is perfect. In this work, the r squared is 0.104. It is significant - but tiny. And, arguably, what you might expect if your measure of attention was based on the first few moments of the ad.

THE MORE YOU LIKE IT…THE MORE YOU TRUST IT…THE LESS ATTENTION YOU PAY TO IT"

This continues the theme he has plied for nearly ten years now; but the research is new.

He starts with the understanding that eye movements are ideal for measuring attention levels. Tiny totally autonomic rapid reflex movements, known as fixation speed. This is an approach which has been used successfully with static stimulus, such as print, in the past. But he uses it for TV ads. And it is from this work that he concludes that the more you like an ad, the less attention you pay to it, and "High levels of emotional content in advertising were significantly correlated at 99.9% with LOWER levels of attention"

This fits perfectly with his theory, yet flies in the face of all the other research into this topic.

Why should this be?

I don't know. But - I suspect the answer lies in one sentence of his papers (e.g.‘KRUGMAN WAS RIGHT – TV ADVERTISING GETS LITTLE ATTENTION BUT BUILDS BIG BRANDS’) . "A few subjects started by watching the screen carefully and followed the action, but most watched in a ‘lazy’ way, exactly matching Krugman’s description of ‘motionless, passive eye characteristics’."

In other words, the thing he was measuring, eye movements, stopped being measurable a few moments into the ad, because the eyes became motionless. So the only way he could distinguish between the levels of attention paid to different ads was through the responses picked up at the start of each ad.

So, if Heath's sentence is an accurate summary, we have the inference that his assessment of the level of attention paid to the ads was actually a measure of the attention paid to the first few moments of the ad.

Can this be right? Surely if this were the case, he would have highlighted the fact in the papers? But none of them refer to it.

There is one other factor here worth reporting on. In his most recent paper, he refers to the r squared for the relationship. This is a measure of how close the relationship is; an r squared of 0 shows there is no relationship between the measures, an r squared of 1 shows there relationship is perfect. In this work, the r squared is 0.104. It is significant - but tiny. And, arguably, what you might expect if your measure of attention was based on the first few moments of the ad.

Heath and Damasio

Robert Heath has referred extensively to the work of Antonio Damasio to support his theories. Since few marketers have read Damasio, few are in a position to challenge Heath's interpretations.

I think the most helpful thing I can say is - if you are interested in this topic, pick up a copy of Descarte's Error and the Feeling of What Happens and form your own judgement.

However, I'll summarise a few key aspects here.

A good place to start is the relationship between emotions and feelings. Heath often uses the terms interchangably or together, which is understandable, since most of us do, but in understanding Damasio, it is vital to understand that he makes a fundamental distinction between the two. I think this is one of the main causes of Heath's errors.

Damasio is clear: "the definitions of emotion and feeling presented here are not orthodox ." (Descartes Error). So what does he mean by these terms?

He identifies three different things.

"a state of emotion which can be triggered and executed nonconsciously;

a state of feeling, which can be represented nonconsciously;

and a state of feeling made conscious " The Feeling of What Happens

So what does he mean by emotion?

"I see the essence of emotion as the collection of changes in body state that are induced in myriad organs by nerve cell terminals, under the control of a dedicated brain system...many of these changes in body state - those in skin color, body posture, and facial expression, for instance - are actually perceptible to an external observer." Descartes Error

"Human emotion is not just about sexual pleasures or fear of snakes....fine human emotion is even triggered by cheap music and cheap movies" The Feeling of What Happens

He says "emotions and core consciousness tend to go together" the Feeling of What Happens

and makes clear that "the biological machinery underlying emotion is not dependent on consciousness." The Feeling of what Happens

He talks of "the here and now of core consciousness" The Feeling of What Happens

And describes "the ongoing process of core consciousness" as being "condemned to sisyphal transiency."

By contrast, he "reserve[s] the term feeling for the experience of those changes" Descartes Error

"Feeling should be reserved for the private, mental experience of an emotion" The Feeling of what Happens

And makes clear; "all emotions generate feelings if you are awake and alert" Descartes Error

He summarises it neatly when he says "flies have emotions, although I am not suggesting they feel emotions." Looking for Spinoza

But what of that curious middle state; "a state of feeling, which can be represented nonconsciously"? He talks about how you can be distracted, but on reflection realise that you have been feeling an feeling for a while. So that, for a period, you have been feeling a feeling without being aware of it.

However, he emphasises; "the full and lasting impact of feelings requires consciousness" the Feeling of what Happens

and "consciousness must be present if feelings are to influence the subject having them beyond the immediate here and now" The Feeling of what Happens

and "feelings perform their ultimate and longer-lasting effects in the theatre of the conscious mind." The Feeling of what Happens

and “when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact,” The Feeling of What Happens

By contrast with the transient impact of emotions, Feelings can have a lasting effect.

"feeling introduced a mental alert for the good or bad circumstances and prolonged the impact of emotions by affecting attention and memory lastingly " Looking for Spinoza

And so, "the human impact of all the above causes of emotion...depends on the feelings engendered by those emotions " The Feeling of what Happens

This is linked with extended consciousness since "extended consciousness is the consequence of....the ability to learn and thus retain records of myriad experiences" the Feeling of what Happens

So “the conscious component extends the reach and efficacy of the non conscious system.”

My summary, then, is that emotions are about changes in the body state, are related to core conciousness, and are transient. But if you are conscious, awake and alert, these emotions will generate feelings. and when these feelings are felt in the conscious mind, they can have their maximum impact and a lasting effect.

So, whenever Heath discusses Damasio and lumps together emotion and feelings, you can be pretty sure he's gone off the rails.

when Heath writes "The definition adopted in this paper uses emotion to signify any stimulation of the feelings, at any level," you know he is heading for trouble.

and when Heath writes "Damasio is saying that if people don’t pay attention then emotions run riot and rule their subsequent behaviour" it highlights just how fundamentally he has misunderstood Damasio's books. (I'm reminded of that great bit of dialogue in A Fish Called Wanda:

Otto: Apes don't read philosophy. Wanda: Yes they do, Otto, they just don't understand it! )

Does the distinction between emotions and feelings matter?

Yes. Because there is almost always a gap between being exposed to an ad and buying a brand. So for advertising to stimulate an emotion of which we are not conscious, its effect will be limited to the time we are exposed to the ad. It is only when these emotions generate conscious feelings that they stand a chance of influencing us later when we are purchasing.

I think the most helpful thing I can say is - if you are interested in this topic, pick up a copy of Descarte's Error and the Feeling of What Happens and form your own judgement.

However, I'll summarise a few key aspects here.

A good place to start is the relationship between emotions and feelings. Heath often uses the terms interchangably or together, which is understandable, since most of us do, but in understanding Damasio, it is vital to understand that he makes a fundamental distinction between the two. I think this is one of the main causes of Heath's errors.

Damasio is clear: "the definitions of emotion and feeling presented here are not orthodox ." (Descartes Error). So what does he mean by these terms?

He identifies three different things.

"a state of emotion which can be triggered and executed nonconsciously;

a state of feeling, which can be represented nonconsciously;

and a state of feeling made conscious " The Feeling of What Happens

So what does he mean by emotion?

"I see the essence of emotion as the collection of changes in body state that are induced in myriad organs by nerve cell terminals, under the control of a dedicated brain system...many of these changes in body state - those in skin color, body posture, and facial expression, for instance - are actually perceptible to an external observer." Descartes Error

"Human emotion is not just about sexual pleasures or fear of snakes....fine human emotion is even triggered by cheap music and cheap movies" The Feeling of What Happens

He says "emotions and core consciousness tend to go together" the Feeling of What Happens

and makes clear that "the biological machinery underlying emotion is not dependent on consciousness." The Feeling of what Happens

He talks of "the here and now of core consciousness" The Feeling of What Happens

And describes "the ongoing process of core consciousness" as being "condemned to sisyphal transiency."

By contrast, he "reserve[s] the term feeling for the experience of those changes" Descartes Error

"Feeling should be reserved for the private, mental experience of an emotion" The Feeling of what Happens

And makes clear; "all emotions generate feelings if you are awake and alert" Descartes Error

He summarises it neatly when he says "flies have emotions, although I am not suggesting they feel emotions." Looking for Spinoza

But what of that curious middle state; "a state of feeling, which can be represented nonconsciously"? He talks about how you can be distracted, but on reflection realise that you have been feeling an feeling for a while. So that, for a period, you have been feeling a feeling without being aware of it.

However, he emphasises; "the full and lasting impact of feelings requires consciousness" the Feeling of what Happens

and "consciousness must be present if feelings are to influence the subject having them beyond the immediate here and now" The Feeling of what Happens

and "feelings perform their ultimate and longer-lasting effects in the theatre of the conscious mind." The Feeling of what Happens

and “when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact,” The Feeling of What Happens

By contrast with the transient impact of emotions, Feelings can have a lasting effect.

"feeling introduced a mental alert for the good or bad circumstances and prolonged the impact of emotions by affecting attention and memory lastingly " Looking for Spinoza

And so, "the human impact of all the above causes of emotion...depends on the feelings engendered by those emotions " The Feeling of what Happens

This is linked with extended consciousness since "extended consciousness is the consequence of....the ability to learn and thus retain records of myriad experiences" the Feeling of what Happens

So “the conscious component extends the reach and efficacy of the non conscious system.”

My summary, then, is that emotions are about changes in the body state, are related to core conciousness, and are transient. But if you are conscious, awake and alert, these emotions will generate feelings. and when these feelings are felt in the conscious mind, they can have their maximum impact and a lasting effect.

So, whenever Heath discusses Damasio and lumps together emotion and feelings, you can be pretty sure he's gone off the rails.

when Heath writes "The definition adopted in this paper uses emotion to signify any stimulation of the feelings, at any level," you know he is heading for trouble.

and when Heath writes "Damasio is saying that if people don’t pay attention then emotions run riot and rule their subsequent behaviour" it highlights just how fundamentally he has misunderstood Damasio's books. (I'm reminded of that great bit of dialogue in A Fish Called Wanda:

Otto: Apes don't read philosophy. Wanda: Yes they do, Otto, they just don't understand it! )

Does the distinction between emotions and feelings matter?

Yes. Because there is almost always a gap between being exposed to an ad and buying a brand. So for advertising to stimulate an emotion of which we are not conscious, its effect will be limited to the time we are exposed to the ad. It is only when these emotions generate conscious feelings that they stand a chance of influencing us later when we are purchasing.

Thursday, 4 December 2008

Heath, Brown and LIP

There is one thing that Robert Heath deserves credit for. And that is reminding the industry that consumers pay very little attention to advertising. It is something that probably most people know, but in the day to day business, it is easy to forget that the ad we have devoted so much time and love to will receive little attention from the general public.

But did Heath say anything new?

In "Low Involvement Processing does the Link Test Measure It?" Robert Heath addresses a critical article by Hollis and DuPlessis, in which they say that the LIP argument is 'not that new'. 'It has little in it that has not been part of the Millward Brown approach to advertising since the 1970s"

Heath was not happy with this suggestion that he was not being original. "Gordon [Brown] talked a lot about high levels of ad awareness and recall being necessary to make ads effective, but he didn't say anything about low-involvement processing," he replied.

This is Heath at his most brilliant. It's true; Brown never referred to LIP. Hollis and du Plessis never suggested he did. Brown was probably not even aware of the phrase. But he had a good empirical understanding of how people attended to advertising.

Let's explore this; because Heath, in an article called "Low Involvement Processing," (Admap 2000) examines the LIP theory, and provides a useful summary. His key conclusions about the LIP theory are copied below. Following each one, I've provided some Brown quotes, from the papers I have to hand, so you can draw your own conclusions.

HEATH:

Consumers do not regard learning about brands as being very important. As a result, most advertising is processed at very low attention levels, using low-involvement processing.

BROWN

"Now, if there is one situation when consumers are not disposed to reconsider their shopping habits, it is while they are watching TV!" How Advertising Affects the Sales of Packaged Goods Brands 1991

"All the evidence is that consumers are very reluctant to ‘engage brain' while watching TV" ‘The Awareness Problem - Attention And Memory Effects From TV And Magazine Advertising’ Admap 1994

"The unmotivated viewing conditions of real life" Lessons from Advertising Tracking Studies 1987

"on air, it seems people won’t work at commercials at all" Lessons from Advertising Tracking Studies 1987

"People watch TV to get away from decisions and be passively entertained. Nor is there any time for thought, for there are no gaps between the ads." Big Stable Brands and Ad Effects Admap 1991

HEATH:

Low-involvement processing is a cognitive process; it is not subconscious or unconscious. It uses very little working memory, which means it is very poor at interpreting messages or drawing conclusions from ads. Instead it simply stores everything as it is recorded, as an association with the brand.

BROWN

I think the value of a brand is not in its meaning, but in all the mental associations in the brain it hooks into. Advertising Effectiveness - The Client, the agency and the Researcher 1994

HEATH:

The way our long-term memory works means that the more often something is processed, the stronger its links to the brand. Thus it is these simple associations, repeatedly stored via low-involvement processing, that tend to define brands in our minds.

BROWN:

"We now have a role for repetition. For long term memories are built by repetition!"

HEATH:

Brand associations can exert a powerful influence on brand decisions, especially if these are made intuitively.

BROWN:

"The process whereby the random, experimental switching that will take place anyway is powerfully channelled by involving advertising memories." How Advertising Affects the Sales of Packaged Goods Brands 1991

"We think that good creative advertising generally affects people's feelings and opinions at some time after viewing the ad, and in ways that are largely subconscious." Plumbing and Shirts 1994

In part two of the article, Heath writes:

My contention is that truly great advertising does something far more important than deliver a rational message, and far more important than entertain: what it does is to establish associations.

BROWN:

What matters is building an association so strong that whenever you think about the brand, images and associations from the advertising come readily to mind Copy Testing ads for Brand Building 1990

I think Heath's error was to confuse terminology with substance. While he may have been the first to apply the term LIP (and later, LAP) to advertising, the idea that advertising was processed with little attention, and the associated implications of this, preceded him by many years.

But did Heath say anything new?

In "Low Involvement Processing does the Link Test Measure It?" Robert Heath addresses a critical article by Hollis and DuPlessis, in which they say that the LIP argument is 'not that new'. 'It has little in it that has not been part of the Millward Brown approach to advertising since the 1970s"

Heath was not happy with this suggestion that he was not being original. "Gordon [Brown] talked a lot about high levels of ad awareness and recall being necessary to make ads effective, but he didn't say anything about low-involvement processing," he replied.

This is Heath at his most brilliant. It's true; Brown never referred to LIP. Hollis and du Plessis never suggested he did. Brown was probably not even aware of the phrase. But he had a good empirical understanding of how people attended to advertising.

Let's explore this; because Heath, in an article called "Low Involvement Processing," (Admap 2000) examines the LIP theory, and provides a useful summary. His key conclusions about the LIP theory are copied below. Following each one, I've provided some Brown quotes, from the papers I have to hand, so you can draw your own conclusions.

HEATH:

Consumers do not regard learning about brands as being very important. As a result, most advertising is processed at very low attention levels, using low-involvement processing.

BROWN

"Now, if there is one situation when consumers are not disposed to reconsider their shopping habits, it is while they are watching TV!" How Advertising Affects the Sales of Packaged Goods Brands 1991

"All the evidence is that consumers are very reluctant to ‘engage brain' while watching TV" ‘The Awareness Problem - Attention And Memory Effects From TV And Magazine Advertising’ Admap 1994

"The unmotivated viewing conditions of real life" Lessons from Advertising Tracking Studies 1987

"on air, it seems people won’t work at commercials at all" Lessons from Advertising Tracking Studies 1987

"People watch TV to get away from decisions and be passively entertained. Nor is there any time for thought, for there are no gaps between the ads." Big Stable Brands and Ad Effects Admap 1991

HEATH:

Low-involvement processing is a cognitive process; it is not subconscious or unconscious. It uses very little working memory, which means it is very poor at interpreting messages or drawing conclusions from ads. Instead it simply stores everything as it is recorded, as an association with the brand.

BROWN

I think the value of a brand is not in its meaning, but in all the mental associations in the brain it hooks into. Advertising Effectiveness - The Client, the agency and the Researcher 1994

HEATH:

The way our long-term memory works means that the more often something is processed, the stronger its links to the brand. Thus it is these simple associations, repeatedly stored via low-involvement processing, that tend to define brands in our minds.

BROWN:

"We now have a role for repetition. For long term memories are built by repetition!"

HEATH:

Brand associations can exert a powerful influence on brand decisions, especially if these are made intuitively.

BROWN:

"The process whereby the random, experimental switching that will take place anyway is powerfully channelled by involving advertising memories." How Advertising Affects the Sales of Packaged Goods Brands 1991

"We think that good creative advertising generally affects people's feelings and opinions at some time after viewing the ad, and in ways that are largely subconscious." Plumbing and Shirts 1994

In part two of the article, Heath writes:

My contention is that truly great advertising does something far more important than deliver a rational message, and far more important than entertain: what it does is to establish associations.

BROWN:

What matters is building an association so strong that whenever you think about the brand, images and associations from the advertising come readily to mind Copy Testing ads for Brand Building 1990

I think Heath's error was to confuse terminology with substance. While he may have been the first to apply the term LIP (and later, LAP) to advertising, the idea that advertising was processed with little attention, and the associated implications of this, preceded him by many years.

A while back, on Nigel Hollis's blog, Robert Heath quoted the following from Damasio:

“The pervasiveness of emotion in our development… connects virtually every object or situation in our experience. Whether we like it or not that is the natural human condition. But when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact, and individuals are also able to reflect and to plan. They have a means of to control the pervasive tyranny of emotion: it is called reason. Ironically, of course, the engines of reason still require emotion, which means the controlling power of reason is often modest” (Damasio 1999: 58).

His interpretation of this quote was:

"So what Damasio is saying is that it is only when we are fully conscious that we can counter-argue the effects of emotion. In other circumstances – for example, when low levels of consciousness are present, as in most TV viewing – emotional influence runs riot."

I find this a fabulous example of how Heath is blind to anything that does not fit with his theory.

He focuses wholly on the part that says "when consciousness is available...individuals are able to reflect and plan," and completely ignores the part of that sentence that says "when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact."

“The pervasiveness of emotion in our development… connects virtually every object or situation in our experience. Whether we like it or not that is the natural human condition. But when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact, and individuals are also able to reflect and to plan. They have a means of to control the pervasive tyranny of emotion: it is called reason. Ironically, of course, the engines of reason still require emotion, which means the controlling power of reason is often modest” (Damasio 1999: 58).

His interpretation of this quote was:

"So what Damasio is saying is that it is only when we are fully conscious that we can counter-argue the effects of emotion. In other circumstances – for example, when low levels of consciousness are present, as in most TV viewing – emotional influence runs riot."

I find this a fabulous example of how Heath is blind to anything that does not fit with his theory.

He focuses wholly on the part that says "when consciousness is available...individuals are able to reflect and plan," and completely ignores the part of that sentence that says "when consciousness is available, feelings have their maximum impact."

Wednesday, 3 December 2008

What does the IPSOS ASI database say about LAP?

In Admap July/August 2006, IPSOS ASI published a paper, using their ad database to explore Heath's hypotheses.

This is hugely useful, since it represents a great opportunity to assess Heath's theories on real data.

Their analysis shows that 'Ads processed with 'ultra' low attention...have a significant impact on brand choice." (I think they define untra low attention as 'those who neither recall nor recognise the ad, but whom we know have been exposed, because they have taken part in the test.')

Fine. I don't know of anyone suggesting that ads with low attention have NO effect.

What is really interesting, though, is their conclusion that "Ads that succeed in being processed with high attention are more than 2.5 times more impactful than ads processed with low attention, and six times more impactful than ads processed with ultra low attention."

Of course, this might be because their database is filled with rational, information driven ads; Heath is explit that his LAP theory does not apply to them; he is talking about emotionally driven advertising. However, the IPSOS ASI chaps go on to say that their research…."suggests that LAP is a slightly more potent force for information-driven ads than for the less informative, more fun and emotionally driven ads."

So, there we go. Another nail in the coffin.

This is hugely useful, since it represents a great opportunity to assess Heath's theories on real data.

Their analysis shows that 'Ads processed with 'ultra' low attention...have a significant impact on brand choice." (I think they define untra low attention as 'those who neither recall nor recognise the ad, but whom we know have been exposed, because they have taken part in the test.')

Fine. I don't know of anyone suggesting that ads with low attention have NO effect.

What is really interesting, though, is their conclusion that "Ads that succeed in being processed with high attention are more than 2.5 times more impactful than ads processed with low attention, and six times more impactful than ads processed with ultra low attention."

Of course, this might be because their database is filled with rational, information driven ads; Heath is explit that his LAP theory does not apply to them; he is talking about emotionally driven advertising. However, the IPSOS ASI chaps go on to say that their research…."suggests that LAP is a slightly more potent force for information-driven ads than for the less informative, more fun and emotionally driven ads."

So, there we go. Another nail in the coffin.

Blinding with Neuroscience

Fascinating piece of research here, showing how adding irrelevant neuroscience to your argument can make it seem more plausible.

http://158.130.17.5/~myl/languagelog/archives/004578.html

http://158.130.17.5/~myl/languagelog/archives/004578.html

Monday, 1 December 2008

Clio and Andrex

I'm sorry, that last post got a bit mathematical.

I'll keep this one simple.

In "Brand Relationships: Strengthened by Emotion, Weakened by Attention" Heath, Brant and Nairn write, "if advertising wishes to build strong brand relationships, it needs to incorporate high levels of emotional content, and this emotional content will be most effective if less attention is paid to it."

They use the campaigns for the Renault Clio and Andrex as examples of "emotional campaigns". They write (OK, let's be honest, I suspect Heath writes), "So we have a situation where two campaigns appear to have worked without imparting any specific facts or information about the brand, but rather by working on the emotions." And refer to how the "Renault Clio and Andrex toilet tissue campaigns which apparently fail to convey informational messages have been astonishingly successful."

So - we have two successful emotional campaigns. In which case, you'd expect consumers to pay little attention to the emotional content. Did they?

Well, no!

To quote the paper again: "the only thing people remembered was "Papa" and "Nicole" and their flirting. And research showed clearly that the factual informational message of "Small car practicality with big car luxury" was completely obscured and never recalled."

And, of Andrex, "The success is therefore attributed not to the message, but to the emotional appeal of the puppy itself. As Stow (1993, p. 53) says, "… this (sales) effect is due in

major part to a Labrador puppy, who has appeared consistently in Andrex' TV advertising since 1972." "

major part to a Labrador puppy, who has appeared consistently in Andrex' TV advertising since 1972." "

(OK, so he doesn't actually say 'people only paid attention to the puppy,' but I'd say it was implied...and even if you disagree, any English reader of this will, by now, have a clear image of that puppy in his/her head. You know you paid attention to it!).

So, a nice straightforward pair of examples from Heath's own work, that completely contradict what he claims.

The reality is, consumers pay attention to, and remember, the emotional elements of campaigns.

How Not to Assess Advertising Effects

In a paper co-authored with Brandt and Nairn, titled "Brand Relationships - Strengthened by Emotion, Weakened by Attention", Heath says: "our evidence shows that if advertising wishes to build strong brand relationships, it needs to incorporate high levels of emotional content, and this emotional content will be most effective if less attention is paid to it."

What was the research? Here is a summary of what they did. "Respondents were first asked the favorability question, and then shown selected video sections of each of the advertisements to ascertain whether or not they had seen them before. The brand favorability scores were then split between those who recognized and those who did not recognize the advertisement. This produces a "shift" in favorability (referred to below as Fav-Shift) that indicates the extent to which the advertising has improved the brand relationship while on air."

Heath's error here is to confuse correlation with causation. He has found a relationship between two variables, and jumped to the assumption that one 'caused' the other.

Let me explain. When respondents say the recognise an ad, it does not mean that they have necessarily seen it. I once saw 80% recognition for an ad which had not aired, because respondents confused it with another ad. And when they say they do not recognise an ad, it does not necessarily mean they have not seen it. They may have seen it and had forgotten having seen it.

This second part is particularly important, because - the more familiar you are with a brand, the more likely you are to notice and remember its advertising. This isn't just an issue of splitting out brand users. If you take non-users, there will be different degrees of familiarity - some will have used the brand in the past, some will have friends who use it, while others will not have heard of it, etc.

So - if you look at a group of people who recognise an ad, they are likely to be more favourably disposed towards it, just because of this phenomenon. It does not mean the advertising has had an effect.

I'll give you an example.

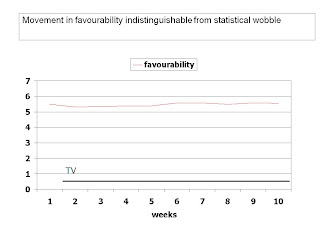

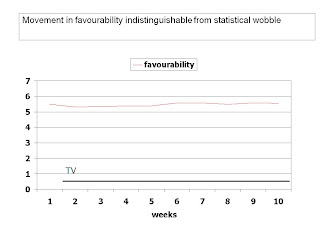

Here is a brand which you've got to feel a bit sorry for. It has had over 1300 GRPs spent behind it over this period. Yet the movement in brand favourability (among non-users) is indistinguishable from the wobble evident at the very start of the chart, before the advertising begins.

Yet, just focusing on non-users, looking at ad-recognisers v non-recognisers, brand favourability among those who did not recognise the ad was 5.65. Among those who did recognise one of the ads it was 6.15. (On a ten point scale) . This would represent a substantial rise in favourability. If you relate this shift to what actually happened on the chart above, you'll see it represents a massive over-statement of the effectiveness of the ad.

What we have here is a variant of the Rosser Reeves fallacy, discovered back in the 60s.

This highlights why comparing the views of recognisers v non-recognisers is not a reliable way to look at the effectiveness of advertising. Even among non-users.

And means that the Heath, Brant, Nairn research was fundamentally flawed and worthless.

P.S. A paper by Heath and Hyder in 2004, "Measuring the Hidden Power of Emotive Advertising"according to Heath, called "into question the value both of recall metrics and

continuous tracking research."

But this research was also based on this recognised/non-recognised analysis. so is equally worthless.

What was the research? Here is a summary of what they did. "Respondents were first asked the favorability question, and then shown selected video sections of each of the advertisements to ascertain whether or not they had seen them before. The brand favorability scores were then split between those who recognized and those who did not recognize the advertisement. This produces a "shift" in favorability (referred to below as Fav-Shift) that indicates the extent to which the advertising has improved the brand relationship while on air."

Heath's error here is to confuse correlation with causation. He has found a relationship between two variables, and jumped to the assumption that one 'caused' the other.

Let me explain. When respondents say the recognise an ad, it does not mean that they have necessarily seen it. I once saw 80% recognition for an ad which had not aired, because respondents confused it with another ad. And when they say they do not recognise an ad, it does not necessarily mean they have not seen it. They may have seen it and had forgotten having seen it.

This second part is particularly important, because - the more familiar you are with a brand, the more likely you are to notice and remember its advertising. This isn't just an issue of splitting out brand users. If you take non-users, there will be different degrees of familiarity - some will have used the brand in the past, some will have friends who use it, while others will not have heard of it, etc.

So - if you look at a group of people who recognise an ad, they are likely to be more favourably disposed towards it, just because of this phenomenon. It does not mean the advertising has had an effect.

I'll give you an example.

Here is a brand which you've got to feel a bit sorry for. It has had over 1300 GRPs spent behind it over this period. Yet the movement in brand favourability (among non-users) is indistinguishable from the wobble evident at the very start of the chart, before the advertising begins.

Yet, just focusing on non-users, looking at ad-recognisers v non-recognisers, brand favourability among those who did not recognise the ad was 5.65. Among those who did recognise one of the ads it was 6.15. (On a ten point scale) . This would represent a substantial rise in favourability. If you relate this shift to what actually happened on the chart above, you'll see it represents a massive over-statement of the effectiveness of the ad.

What we have here is a variant of the Rosser Reeves fallacy, discovered back in the 60s.

This highlights why comparing the views of recognisers v non-recognisers is not a reliable way to look at the effectiveness of advertising. Even among non-users.

And means that the Heath, Brant, Nairn research was fundamentally flawed and worthless.

P.S. A paper by Heath and Hyder in 2004, "Measuring the Hidden Power of Emotive Advertising"according to Heath, called "into question the value both of recall metrics and

continuous tracking research."

But this research was also based on this recognised/non-recognised analysis. so is equally worthless.

Uri Geller

In the 1970s, an Israeli called Uri Geller generated massive publicity around the world by claiming to be able to bend metal with the power of his mind.

Many scientists took his claims seriously. His abilities were investigated at science labs, and papers were published in scientific journals.

Many believed his claimed abilities were genuine and talked about a paradigm shift.

Yesterday at a convention of magicians in London, he is reported to have admitted, "I had the idea and cheekiness to call it psychic, in fact all I wanted was to be rich and famous."

This seems to be an appropriate day to start writing about the Advertising theories of Robert Heath.

I'm not going to suggest that he deliberately set out to hoodwink the industry. But the flaws in his thinking are so glaring that it beggars belief that industry practitions have not criticised his work more rigorously than they have done to date.

It is likely to leave the impression with the less experienced people within the industry that he was right, in the same way that the lack of criticism of Uri Geller led many to assume that he was right.

I want to address that in this blog.

Many scientists took his claims seriously. His abilities were investigated at science labs, and papers were published in scientific journals.

Many believed his claimed abilities were genuine and talked about a paradigm shift.

Yesterday at a convention of magicians in London, he is reported to have admitted, "I had the idea and cheekiness to call it psychic, in fact all I wanted was to be rich and famous."

This seems to be an appropriate day to start writing about the Advertising theories of Robert Heath.

I'm not going to suggest that he deliberately set out to hoodwink the industry. But the flaws in his thinking are so glaring that it beggars belief that industry practitions have not criticised his work more rigorously than they have done to date.

It is likely to leave the impression with the less experienced people within the industry that he was right, in the same way that the lack of criticism of Uri Geller led many to assume that he was right.

I want to address that in this blog.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)